Banking sector extraordinary privileges

Banks benefit from an extraordinary privilege: in times of impending systemic financial crises, governments act as guarantors of last resort for banks’ financial obligations. This privilege is not paid, at least not directly.

Banks are subject to taxes, like other corporations. In addition, some countries such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, and Spain have recently imposed extraordinary levies on banks. The justifications provided by the governments for these levies and the ECB’s critics avoided to refer to these taxes as a charge for the above-mentioned extraordinary privilege of banks. Instead, they seem to be primarily motivated by fiscal needs.

Government guarantees are necessary

Governments worldwide provided explicit or implicit guarantees to financial institutions and creditors in response to the 2007 global financial crisis. This governmental role in offering a safety net to the financial sector is essential to prevent the systemic collapse of the economy for two reasons:

First, to prevent systemic collapse. Financial institutions are closely linked, and their failure can cause a cascading effect leading to a severe economic crisis. Governments guarantee financial institutions and creditors to restore confidence and avert a financial system collapse.

Second, to sustain essential institutions. Some financial institutions are “too big to fail” or have significant importance for other reasons, and their failure could cause severe economic damage. Banks are important for lending, deposits, and payments.

To safeguard the broader economy and to protect households considered particularly vulnerable, governments have become the guarantor of last resort for private financial claims involving these institutions.

The moral hazard dilemma

This role gives rise to implicit guarantees which have economic value but are not priced. Such guarantees in turn induce moral hazard, where banks take excessive risks, expecting government rescue if they fail. The 2023 SVB and Credit Suisse cases show that this risk is real despite a decade of regulatory reforms. Economists propose several additional solutions to address this risk, including the following.

Charging Fees

Some economists suggest governments impose fees for financial guarantees, considering risk and potential fiscal costs. This approach encourages institutions to exercise caution as they essentially pay for the safety net. This concept can be likened to charging admission to a poker game and credibly announcing that any losses incurred remain private. Players can be expected to become more prudent, knowing that there is a cost involved.

Strengthening fiduciary rights of taxpayers

Another proposed solution is to ensure that those who bear the financial burden of bailouts have a voice in determining the fate of financial institutions that take excessive risks. Kane (2014) argued that taxpayers, de facto, are coerced equity investors with unlimited liability, which is why corporate law should be modified to accord taxpayers with the same fiduciary rights to prudent stewardship that the law already gives to explicit shareholders.

Transparency and accountability

Transparency can hold financial institutions accountable by revealing guarantee terms and beneficiaries and monitoring their effects. Reporting this information to the public and parliament can increase oversight, ensuring that government guarantees are used responsibly. An example is budgetary practice, which explicitly reports the potential contingent liabilities arising from the banking sector, as in Australia. Public debt managers also make these estimates.

Tweak the mix of policy responses?

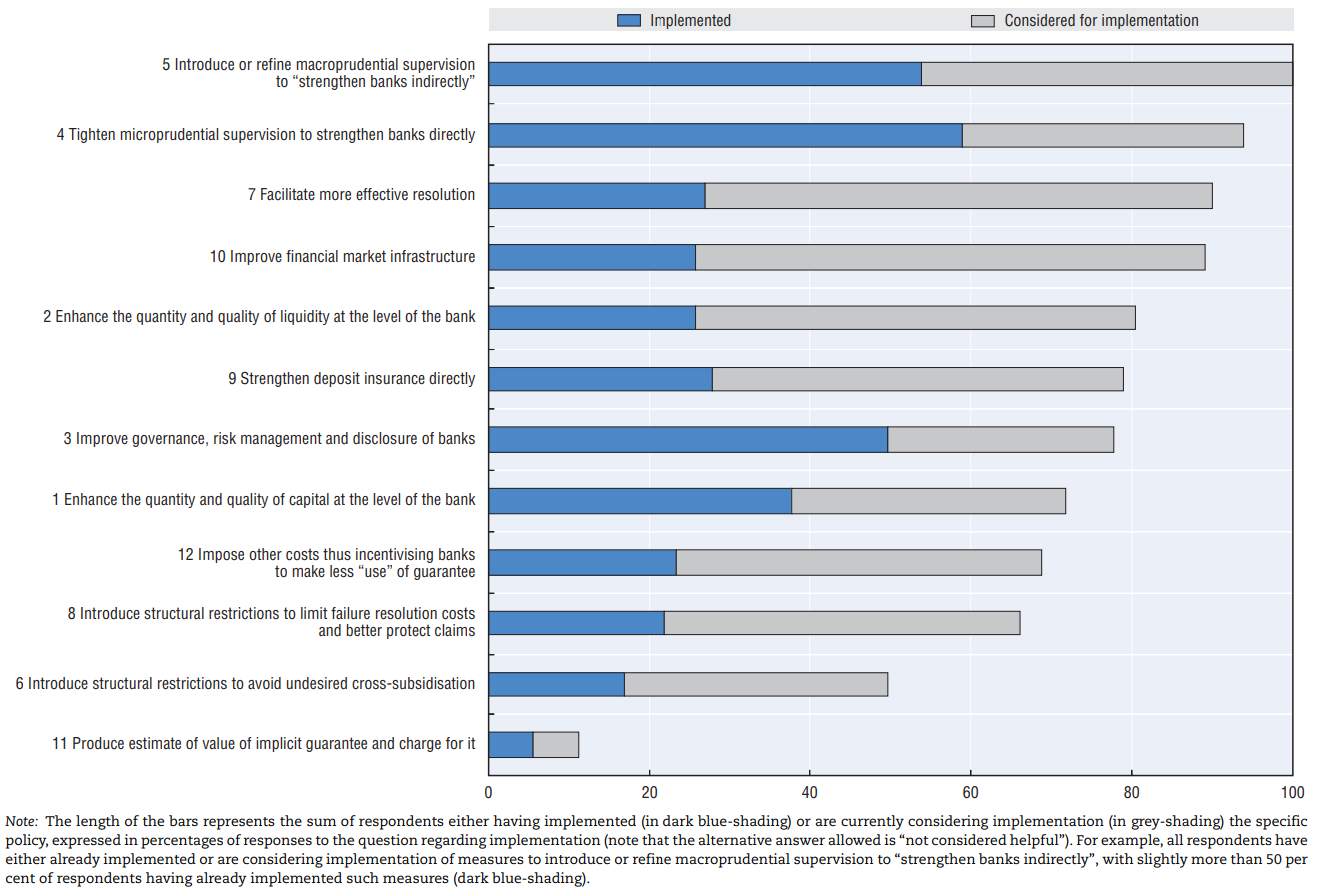

Governments hesitate to assign price tags and to enhance transparency about contingencies. A decade ago, the OECD surveyed policymakers on the best way to limit implicit guarantees of bank debt. The survey found that a mix of policy measures was considered helpful. Common policy measures include capital/liquidity standards, tighter supervision, and improved bank failure resolutions. The least popular option was to “produce estimates of the value of implicit guarantee and charge for it” (Figure 1). While putting a price on implicit guarantees to discourage their “use” is conceptually attractive, as is enhancing transparency, policymakers fear such measures further entrench ‘bail-out’ expectations.

Recently imposed extraordinary bank levies do not seem to be an attempt to charge a “user fee” for the extraordinary privilege that banks receive as a group. Instead, fiscal pressures seem more relevant. Design and implementation of an economic “user fee” would require closer collaboration between the various institutions that provide the financial safety net, that is regulators, treasuries, central banks, and deposit insurers. Both within and across national borders.

Figure 1: Categories of policies to limit the value of implicit bank debt guarantees

Source: Responses from 35 countries to OECD survey (Figure 2, p. 15).